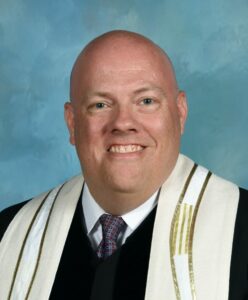

By The Rev. J.C. Austin

As many of you know, international travel has been a passion of mine throughout my entire adult life, and I have both worked hard and been fortunate enough to have seen many parts of the world at this, including significant portions of six continents (Antarctica has been elusive so far, but I’ll get there).

And almost all of that travel has been independent rather  than with guides or packages, both because it’s far, far cheaper that way and because part of what I enjoy most is the freedom to not only set and change my itinerary, but to simply wander and explore and find my own way and even get lost on occasion. Well, getting lost hiking in the Drakensberg mountains of South Africa as the sun was going down and the leopards were coming out to hunt wasn’t so great, but it made for a good story…that I’ll have to tell you another time.

than with guides or packages, both because it’s far, far cheaper that way and because part of what I enjoy most is the freedom to not only set and change my itinerary, but to simply wander and explore and find my own way and even get lost on occasion. Well, getting lost hiking in the Drakensberg mountains of South Africa as the sun was going down and the leopards were coming out to hunt wasn’t so great, but it made for a good story…that I’ll have to tell you another time.

Because the point is that I think the biggest difference between being a traveler and being a tourist is, well, the actual travel part between the postcard sights and experiences, not those experiences themselves. Now, I’m not deriding tourism. There are plenty of good reasons to be a tourist rather than a traveler.

You don’t have the time to travel independently, which always takes a lot longer; you have mobility issues from preventing you doing that; or you just don’t have the patience or endurance or energy to put up with all the uncertainty and craziness that independent travel requires, or at least don’t want to do so. But the simple fact is, most of my best travel stories are about traveling itself, not about the sights I was traveling to see or the experiences I was traveling to have.

For example, some of you have heard parts of my story of taking local buses for 18 hours across Uganda to go see the mountain gorillas there; the gorillas were amazing to see, but the real story is about the trip it took to get to them. But I couldn’t tell the whole story in a single sermon, because there are at least four distinct chapters that each take a while to tell and not all of them are relevant to one given sermon.

You may remember me telling the story in a sermon of trying to get to that bus when my pre-arranged taxi didn’t show up, and walking out on the road in the dark when a stranger’s car pulled over in front of me and offered me a ride that I wasn’t sure I should accept; that’s the first chapter. Then there’s the story of getting on the bus and discovering what the definition of a “full” bus is in Uganda (the short version is it included people sitting in each other’s laps, on the headrests, and hanging on the running boards on the outside, in addition to actual seats).

And the story of the bus getting underway and discovering that it wasn’t actually going to our destination, but only “near” it because of road problems, and I’d have to get dropped in the jungle and figure out how to go the rest of the way on my own. Then there was the story of getting in the back of a pickup truck to go those final 30 miles after the bus ride ended, over a broken dirt road with at least 30 other people crammed into the bed along with their luggage, which resulted in two flat tires in a truck that only had one spare, the second of which happened in the middle of the jungle.

And then there’s the end of the story, which you also may have heard me tell, when I finally arrived at the local campground in the mountains late that night to discover the restaurant had closed and I hadn’t eaten anything all day except an apple and a hard-boiled egg at 4:30 am, and was almost crying from hunger until the manager took pity on me and made up some spaghetti in the back that tasted like the best pasta I had ever had because I was so hungry.

See what I mean? Just the summary is still a pretty good story, but we’d be here until early afternoon if I actually told you the whole thing in the detail it deserves!

Even so, that trip was still only about 18 hours, so I can only imagine the stories that the magi would have had in journeying from their homes in modern-day Iran all the way to Bethlehem. And we do have to imagine them, because Matthew tells us essentially nothing of that journey. But there must have been a lot of stories.

There were no package tours they could have booked back then; no planes or trains or even luxury camels to charter. So their journey would most definitely have been independent travel, and they would have been lucky in places to find a broken dirt road to follow. One of my favorite poems is T.S. Eliot’s “Journey of the Magi,” in which he imagines how one of the magi would have looked back on the journey and described it:

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

And the camels galled, sorefooted, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow….

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

and running away, and wanting their liquor and women,

And the night-fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

As a traveler, I have to say that Eliot’s description has a deep sense of truth to it, a truth that we usually don’t consider when we hear the familiar story in Matthew because Matthew doesn’t reference anything about their journey other than the simple fact that they took one: “In the time of King Herod,” he says, “wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, ‘Where is the child who has been born King of the Jews? For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage.’”

The actual journey, the travel part of their travels, is completely skipped in Matthew’s account, despite the fact that there were almost certainly a number of very good stories that could have been told.

I wonder if that might actually be why Matthew avoided telling those stories. It’s the same reason I didn’t tell you today about getting lost in in the dark with the leopards in the Drakensberg mountains; sometimes a good, interesting, entertaining story can actually lead you away from what’s really important, from what needs to be told and heard.

For Matthew, that isn’t the details of the journey that the magi took. What is important to Matthew is, first, that they took that journey; that matters far more that the nature of that journey. The magi might have taken a rickety local bus or flown over on a charter jet, it doesn’t actually make a difference to what’s really important: that they came at all. Matthew, among the four gospels in the Bible, is the most focused on the fact that Jesus, his life, and his ministry cannot be understood apart from Judaism.

Matthew goes out of his way to explicitly affirm Jesus’ identity as a faithful Jew. In fact, one of the first things he records Jesus saying during the Sermon on the Mount, his most important and comprehensive teaching, is “Do not think I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets,” the commandments and covenants of God for the Jewish people that are mandated in the Hebrew Scriptures, in other words; “I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matthew 5:17).

Which is what makes the story of the magi coming to pay homage to Jesus, which Matthew alone describes in the New Testament, all the more remarkable and important. Because the magi are anything but faithful Jews. From the language used to describe them, they probably came from the Parthian Empire, which controlled the northern part of modern Iran as well as parts of Iraq, which would have ironically included what used to be Babylon, which of course destroyed Jerusalem and took the elites of the Israelite people into exile for several generations.

But now these magi from that same region are coming, they say, to pay homage to the king of the Jews. And religiously, they are almost certainly Zoroastrian; Zoroastrians worship a god of wisdom, have priests called magi, or “wise ones” (it’s where the word comes from), and those priests are learned in astronomy and astrology, so they would both be paying attention to unusual astronomical activity and would see it as spiritually significant. All of that makes total sense.

What’s unexpected, even shocking, is that they felt the need to come see and honor Jesus instead of just noting it in passing to each other like, “hey, looks like the Jews have got themselves a new king,” the way that we might have read about the recent presidential election in Chile. But they see it as an event that involves them, something that they should respond to, not simply notice. And by making the long journey and paying Jesus homage, they make the point that Jesus is not simply the Messiah promised to the Jewish people, but the one who is sent because God so loved the world, as the gospel of John puts it; the whole world, and all of its peoples.

That’s why their visit is worthy of its own annual holiday on the Christian calendar, Epiphany Sunday, because the word epiphany means both a moment of revelation and/or insight and the manifestation of a divine being, and both of those things are happening in their visit. Jesus’ birth is the manifestation of the Son of God in human form, and he is revealed to the magi as such in their visit and, indeed, in the sign of the star that they witnessed, and discerned the significance of, and followed its call in the first place.

Astrology is not something most people take seriously these days, and there are some good reasons for that. A lot of contemporary astrology is little more than petty fortune-telling, with assurances so vague that they can be applied to almost anything: “An unexpected business opportunity may be coming your way; a new connection may be the seeds of romance,” that sort of thing.

But human beings have viewed the stars as guides to follow for millennia; they are literally the single most significant resource for physical navigation in the history of the world, and it’s a short distance from that to using them for spiritual navigation, as well. Now, neither Judaism nor Christianity have a spiritual tradition of astrology, so Matthew is not calling us to do that in this story, and neither am I.

But that’s actually part of the significance of the Epiphany story: God invited the magi to play a key role in God’s overarching story of salvation for the world, to come and witness the manifestation and revelation of the Christ child as the first of those beyond God’s covenantal people, the Jews, by showing them a sign that connected with their own traditions that they could notice and recognize and respond to as they were going about their normal lives in their own context.

That’s the invitation that Epiphany still offers today: not simply noticing that Jesus was born, but recognizing the all-inclusive importance of that, paying attention to the signs as we go about our normal lives, and then responding to them. Epiphany comes early in the Christian new year and even earlier in the secular one, just a few days after New Years’ Day (we’re observing it today, but the actual holiday is January 6 every year, after the twelve days of the Christmas season).

In recent years, many churches have adopted the tradition of Star Words in conjunction with Epiphany, which we are doing today for the first time. The idea of a Star Word is that it is a sign to look for as you go about your normal life throughout this year, to guide you in life and faith and help you respond to the promise and call of Jesus Christ as the salvation of the world. The words are sometimes simple, sometimes complex, but always rich and provocative.

Some churches do this “blindly” by drawing words out of a bowl or bag. But we liked the idea of spreading them out as a constellation and letting you see what sign you notice calling to you, the way the magi would have noticed the star for the Christ child. And so that’s what we will invite you to do in just a few minutes in this service; we’ll explain more when we get there.

The point, though, is to give you a sign to lead you in faith through the year, and I think we could all use all the guidance we can get as we struggle to travel though the chaos and confusion of these days we find ourselves in.

And as you do, your Star Word will help you connect those experiences with the larger story of God’s loving and saving grace that is poured out for us all, every day and in abundance, that Epiphany invites us to remember and claim and live out, so that we ourselves are changed by the experience and brought closer to God in understanding and action, and be signs of light in the world ourselves.