By The Rev. Lindsey Altvater Clifton

Last Sunday, we celebrated the gifts of Mary and her courageous, prophetic song of praise, the Magnificat. We considered with awe and wonder her “yes” to bearing God’s love for the world in spite of all the challenges that meant. This Sunday, we look to an understated member of the Holy Family, Joseph. We don’t sing songs about him or his role in parenting Jesus or nurturing his family, but there is much to be said about him.

Matthew’s gospel account says that in the midst of the  miraculous scandal that is Mary’s pregnancy, a dream changes everything. Just when Joseph has made up his mind to let Mary go quietly, an angel shows up while he sleeps to say, “Don’t be afraid. This is all part of the plan. Love can’t wait. Prepare him room. Be his chosen family. Name him Jesus, Emmanuel, God is with us.” And with great courage, Joseph gets on board and does as he has been guided.

miraculous scandal that is Mary’s pregnancy, a dream changes everything. Just when Joseph has made up his mind to let Mary go quietly, an angel shows up while he sleeps to say, “Don’t be afraid. This is all part of the plan. Love can’t wait. Prepare him room. Be his chosen family. Name him Jesus, Emmanuel, God is with us.” And with great courage, Joseph gets on board and does as he has been guided.

As I think about this, it sort of blows my mind a little. It also makes me think that this isn’t the first time Joseph has demonstrated courage. And we certainly know it won’t be the last. As theologian Mary Daly reminds us, “Courage is like – it’s a habitus, a habit, a virtue: We get it by courageous acts. It’s like we learn to swim by swimming. We learn courage by couraging.”

What I love about this story is that it reframes what we often thing of as courage, and it invites us to practice it in new ways. Usually, our notions of courage are about strength or heroics. But that’s not what we see here. Instead, the hallmarks of Joseph’s courage are vulnerability and imagination.

Researcher, professor, and author Dr. Brené Brown has written much about the relationship between vulnerability and courage. For an introduction to her work, I commend to you her Netflix special The Call to Courage. But for today, I’ll share just a couple bits of her work beginning with this: “The root of the word courage is cor – the Latin word for heart. In one of its earliest forms, the word courage had a very different definition than it does today. Courage originally meant ‘To speak one’s mind by telling all one’s heart.’…Ordinary courage is about putting our vulnerability on the line. In today’s world, that’s pretty extraordinary.”

So what, then is vulnerability? She continues, “Vulnerability is not about winning or losing. It’s having the courage to show up even when you can’t control the outcome.” In addition, she writes this: “Vulnerability is uncertainty, risk, emotional exposure. There’s no courage without vulnerability.”

Uncertainty, risk, emotional exposure. Yikes, y’all… That takes courage, for sure! And as I imagine a young Joseph having just changed his mind to remain with his young fiancé and her unborn child who isn’t his, the uncertainty, risk, emotional exposure… the vulnerability of that decision… is enormous. It’s senseless, really. Absurd. Preposterous. Impossible.

But he does it, anyway. Why in the world would an angel-visit dream (that could’ve just been indigestion for all he knew) be enough for him to embrace such a path? I think it’s because courage, in all its vulnerability, also requires imagination. Joseph, it seems, could see beyond the current reality into what was possible. He could imagine beyond biological family to chosen family. He could imagine the unimaginable… that all of this just might be true, that God’s love might be so unstoppable and irresistible that it was going to be born by Mary and born into the world in the most vulnerable, unimaginable way of all.

Even for us today, to say yes to such a story requires this same kind of vulnerable, imaginative courage. Like Joseph, we have to be able to envision what’s possible on the other side of the uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure of a faith that calls us into deep relationship with God and with others. Because as biblical scholar Dr. Karoline Lewis reminds us:

The promise of Jesus’ birth and Jesus’ name is, “God is with us,” not “God is with you.” That first-person plural pronoun establishes how God in the flesh chooses to be in the world. Not for our individual gain or theological guarantee. Not for our personal salvation. But to remind us of who we are meant to be and supposed to be — people in community, with God. People oriented toward the other because of God.

“God with us” corrects “God is for me.” “God with us” corrects “God is for us.” “God with us” helps us remember that when we do turn away from others, we turn away from those who need us and those whom we need. We turn away from accountability and responsibility.

As I’ve reflected on those words, I can’t help but wonder: What if Joseph had turned away? Surely, his path would have been easier. Instead, we see that courage as vulnerability and imagination require us to turn toward all the messiness and complexity that is loving God and loving neighbor.

Indeed, there are so many contemporary implications for our own call to such relational vulnerability and imagination. Too often, we soften the deep challenges of the Christmas story to fit our plush or cartoon nativities or our whitewashed ideas about how cozy the Holy Family must’ve been alongside the critters in the manger. But such a powerful, peculiar, impossible story calls us to more than that.

Shortly after today’s passage, Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus takes a harrowing turn. The mystical magi find their way to Bethlehem, and shortly after they leave, another angel comes to Joseph with a vision that requires yet more courage. Already displaced from Nazareth, already with no place to stay in Bethlehem to be registered for the census (at least according to Luke’s telling of the story), the angel says to Joseph, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and remain there until I tell you; for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.”

Amazingly, Joseph does it. “Then Joseph got up, took the child and his mother by night, and went to Egypt.” Talk about vulnerability and imagination. To escape Herod’s threats of death, this brand new family sets out all the way across Israel and the Sinai Peninsula for Egypt. This is no ordinary story; rather it is an extraordinary, unimaginable one. Yet we make ourselves vulnerable to risk believing and we choose imagination anyway.

If that is true of this ancient story, I wonder how we might see God-with-us in this present age. And I wonder how we might embody Joseph’s courageous vulnerability and imagination to recognize those in our midst who might just remind us of the Holy Family if only we’d allow ourselves to see them—families displaced from their home countries; families experiencing poverty; families on the run from violence; families in need of a warm, safe, place to live.

If we are willing and able to imagine such an extraordinary possibility – that our neighbors in need bear the image and face of God – how might that challenge us and change us and call us to courageous relationship and visionary action?

To stir our individual and collective imaginations about how such loving courage can’t wait if we are to build God’s home here and now, I want to invite us to see the Holy Family anew. We’ll view a series of images depicting Joseph, Mary, and Jesus. I’ll share the title and artist or community connected to each one, and then we’ll spend a few moments considering it in silent reflection. May our hearts be open and courageous so that we might encounter God.

- An icon called Refugees: The Holy Family by Catholic iconographer Kelly Latimore

- Refugees: La Sagrada Familia also by Kelly Latimore

- A Nativity at Claremont United Methodist Church in Claremont, CA

- From a production of Langston Hughes’ classic musical drama Black Nativity at The Karamu House in Cleveland, OH

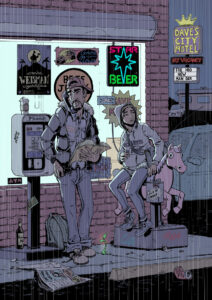

- José y Maria, a comic by Everett Patterson

- Finally, one more of Kelly Latimore’s icons, this one called Holy Family of the Streets

Dear ones, with Joseph’s vulnerability and imagination, may we be courageous enough to experience this ancient story in new ways so that we might be moved to present action. For love can’t wait. Our neighbors can’t wait. We need to draw closer to God’s intended home here and now! So may we have the courage to hear and live these final words from Benedictine nun, Sister Ruth Fox:

May God bless you with discomfort at easy answers, half-truths, and superficial relationships, so that you may live deep within your heart.

May God bless you with anger at injustice, oppression, and exploitation of people, so that you may work for justice, freedom, and peace.

May God bless you with tears to shed for those who suffer from pain, rejection, starvation, and war, so that you may reach out your hand to comfort them and to turn their pain into joy.

And may God bless you with enough foolishness to believe that you can make a difference in this world, so that you can do what others claim cannot be done. [This day and each day. Amen.]